By: James Kennedy | Roar | EastLeeNews.com

Last year, an unexpected post surfaced in my social media feed—not as a distraction, but as an invitation. The Okeechobee Main Street Gallery was advertising work by Hobby Campbell, Brad Phares, and Eldon Lux. What stopped me was not just the quality of the paintings. It was the subject matter: Florida’s cracker cowboys and the rural landscapes that shaped them.

These are subjects deeply rooted in Florida’s history and too often ignored in Florida’s present. Most Floridians are at least passingly familiar with the Highwaymen. Their story matters and deserves its place. But that is not the story being told here. What I found instead was a quieter, largely under-recognized group of artists documenting both the history and the present-day reality of Florida’s working cowboys, cow hunters, and cattle culture.

These are not romanticized figures. They are working people, descendants and continuations of a cattle tradition that stretches back more than 500 years and forms the bedrock of Florida’s agricultural identity. Spend time around real ranch country and you learn quickly that Florida’s cowboy tradition is not a costume. It is work.

That realization led me to sit down with Eldon Lux. Eldon and his wife, Lynn, met me at the Okeechobee gallery, where we talked for more than an hour. We later continued the conversation over lunch, talking for another hour. It was easy, unguarded, and full of stories. They are down-to-earth, humble people, deeply engaged with the world around them. But our focus was Eldon’s art: how he came to Florida, why he paints what he does, and what it means to create work that carries both responsibility and reverence.

Eldon is originally from Nebraska. He grew up in ranch country, earned an animal science degree, and lived a life shaped by cattle, horses, weather, and land. Like many ranchers of his generation, he lost everything during the economic upheavals of the 1980s. Ranching ended, but the work did not. Leatherwork, saddle repair, farrier work, and training horses were not side jobs. They were continuations of a way of life.

Art was never separate from that world. It grew out of it. Florida became home not by accident, but by recognition. Eldon saw in places like Okeechobee, Osceola County, and the Kissimmee Prairie a working landscape that mirrored the life he knew and respected. The cattle were different. The dogs were different. The land and the tactics were different. But the rhythm of the work and the bond between people, animals, and place felt familiar.

At one point he said something that stuck with me: everything that is normal changes about fifty miles. If you have spent time in rural Florida, you know exactly what he means. North Florida is not ranched the way central Florida is. Osceola is not Okeechobee. Even within the same region, what works on one place might get you run off the next. You learn by watching, adapting, and keeping your mouth shut long enough to understand how things really work.

That philosophy carries straight into Eldon’s paintings. He does not paint nostalgia. He paints what he knows and what he has lived. His work is grounded in experience and careful observation, shaped by memory and informed by respect. He talks about other artists, including Hobby Campbell, Sean Sexton, and others, with genuine admiration. There is no posturing and no need to elevate himself by diminishing anyone else. His work exists as part of a broader, largely under-recognized body of art created by people who know this life firsthand.

He is also blunt about the craft itself. Eldon rejects the idea of being “self-taught.” Like every serious artist, he learned by studying others, by looking closely, borrowing freely, and figuring things out through persistence. Over time, his style has loosened. Detail has given way to mood. What matters now is not painting every palm frond, but capturing what a moment feels like, the tension at a water’s edge, the awareness of unseen danger, and the quiet weight carried by a working cowboy.

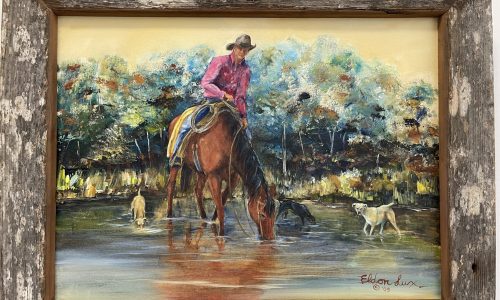

One of the strongest examples of that approach is a piece called Watchful Eye, a moment at the water where dogs drink, horses stand, and the cowboy’s attention does not drift. The scene is not about the background. It is about what you cannot see. It is about why Florida cow work is different. It is about why a man watches the water like it might reach up and take something.

Eldon also paints with a long view of Florida’s cattle story. One major piece, 500 Years, traces the continuity of Florida’s cattle culture, from early Spanish arrival through the evolution of the working cow hunter and into the present-day cracker cowboy. It is part realism and part memory, and that blend is the point. It is not heritage as decoration. It is history as lived experience, rendered by someone who respects what the work costs.

At its core, Eldon’s work functions as a living record. His paintings preserve moments that are disappearing, not as relics of the past, but as realities that still exist if you know where to look. In doing so, they hold onto something essential, not just how Florida once was, but how it continues to be shaped by land, labor, and people who work with humility and resolve.

This is not loud history. But it is real history. And if we do not pay attention now, we will be left pretending we did not watch it disappear.